A Philosophical Framework for Understanding and Preaching Kṛṣṇa Consciousness with Fidelity to Vaiṣṇava Epistemology

By Ajit Krishna Dasa

Introduction: The Pre-experiential Ground of Knowing

This paper presents a comprehensive framework for understanding Vaiṣṇava epistemology, intended especially for those engaged in the serious intellectual preaching work of Lord Caitanya Mahāprabhu’s mission. We will explore how knowledge begins not with inquiry, but with revelation—how śabda (divine testimony) is not a supplement to reason or perception, but the very ground upon which all rational thought, moral judgment, and empirical investigation rests.

We will proceed in ten parts:

- Knowledge as Innate and God-Given

- Immediate, Not Constructed, God-Consciousness

- The Three Pramāṇas in Vedic Epistemology

- The Conditional Validity of Pratyakṣa and Anumāna

- Śabda: The Epistemic Foundation

- The Transcendental Argument for God

- Preaching Implications: Recovering Innate Theism

- A Critique of Godless Epistemologies

- Śabda or Skepticism: The False Neutrality of Secular Reason

- The Moral Suppression of Divine Knowledge

The framework presented here is not merely theoretical; it is intended to serve both as a foundation for understanding and as a strategy for preaching—showing that it is not only scripturally true but logically necessary to begin with God and śabda if one wishes to know anything at all.

The distinction between two epistemological approaches—āroha-pantha, the ascending method based on human speculation and empiricism, and avaroha-pantha, the descending method of receiving knowledge from a higher, divine source—is crucial to understanding the foundations of Vaiṣṇava epistemology. Vaiṣṇava philosophy decisively rejects the āroha-pantha as insufficient and ultimately self-defeating. True and reliable knowledge, especially concerning metaphysical realities and the nature of God, must come through the avaroha-pantha—revelation through śabda (authoritative testimony), which in this context refers to the descending process of knowledge received from a perfect source. This descending process affirms that genuine knowledge is received, not constructed; bestowed, not invented.

Within the Vedic tradition, particularly as expressed through the Vaiṣṇava śāstric corpus, epistemology is not regarded as a matter of mere empirical accumulation or rational abstraction. Rather, it is ontologically grounded in the very constitution of the jīva (the individual self) and its relationship with the Supreme Person, Śrī Kṛṣṇa.

At the heart of Vaiṣṇava epistemology lies the assertion that knowledge is not fundamentally acquired; it is awakened. While it is true that some forms of knowledge—such as linguistic, cultural, and empirical learning—are acquired through experience, all such acquisition presupposes a deeper foundation. That foundation is the divinely imparted epistemic structure inherent to the jīva. In other words, all acquired knowledge is only possible because it rests upon perfect, innate, God-given knowledge that enables the soul to perceive, interpret, and integrate information meaningfully. That is to say, the living entity is not born epistemically empty. Rather, knowledge of God and the epistemic grounding needed to navigate His creation—the very principles that make all further knowing possible—is eternally present in the jīva.

This epistemic orientation forms the foundation of the Vaiṣṇava understanding of revelation (śabda), perception (pratyakṣa), and inference (anumāna), establishing that all valid forms of knowing depend upon this initial divine illumination—a personal and purposeful gift from the Supreme Lord, not merely an abstract metaphysical principle. This serves as the philosophical groundwork for establishing Kṛṣṇa consciousness as the only coherent and complete worldview.

As a corollary to this, the structure of Vaiṣṇava epistemology leads naturally to a kind of transcendental critique—demonstrating that any worldview which does not accept God as ontologically prior, and śabda as epistemically foundational, ultimately collapses into incoherence. In other words, it highlights the fact that the denial of God entails the loss of the very foundations necessary for knowledge, reason, or meaning to be possible at all.

1. Knowledge as Innate and God-Given

The first form of śabda that the living being receives is not external, but internal—what may be termed innate śabda. This refers to the eternally present spiritual knowledge embedded within the soul by Kṛṣṇa. It is this divine imprint that enables the jīva to not only recognize the Supreme Lord but also to function meaningfully within His creation. The soul is not born as a blank slate; it arrives with a pre-installed framework for truth, goodness, personhood, and rationality—all emanating from the Lord Himself.

The Bhagavad-gītā (15.15) declares:

sarvasya cāhaṁ hṛdi sanniviṣṭo, mattaḥ smṛtir jñānam apohanaṁ ca

“I am situated in everyone’s heart, and from Me come remembrance, knowledge, and forgetfulness.”

This verse is pivotal. It affirms that epistemic faculties themselves—memory, knowledge, and the cessation thereof—are gifts from Kṛṣṇa, who, as Paramātmā, inhabits the heart of every living being. The implications are significant and invite further exploration: the structure of Vaiṣṇava epistemology suggests that the very possibility of knowing may ultimately depend upon the existence of God, a conclusion that subsequent sections will more fully establish.

By describing knowledge as innate, Vaiṣṇava epistemology is not asserting that all factual content is encoded at birth, but that the structural capacity for knowing—the presuppositions, categories, and faculties required for any truth claim, whether empirical or metaphysical—is embedded in the living being by divine design. Human beings intuitively operate with concepts of causality, moral responsibility, personal agency, and abstract reasoning long before formal education. Such capacities are not explained at all by social conditioning or material evolution; these frameworks fail to account for the a priori categories of rationality, morality, and selfhood. They are, rather, metaphysical gifts—divine endowments that reflect the Lord’s eternal presence within the living being.

In this view, epistemology is not merely a methodological concern; it is an ontological necessity rooted in divine immanence. The jīva possesses embedded perfect knowledge because the Supreme Knower is within. Even the urge to question, the capacity to reason, and the ability to synthesize perception are made possible by His sanction.

Thus, the act of knowing precedes any empirical input and depends fundamentally on the presence of divine consciousness within. It is this internal divine infrastructure that makes cognition, interpretation, and learning possible at all—not merely external observation or sensory data.

Were this divine infrastructure absent—were the living entity not endowed with innate, God-given knowledge—the very preconditions for epistemology would be missing. One would have no reliable means to distinguish truth from error, no standard of reason beyond subjective impressions, and no metaphysical anchor for the cognitive faculties. In such a state, the jīva would be epistemically inert, unable to form coherent thoughts or form sound judgments. Thus, the presence of innate divine knowledge is not an added benefit—it is an absolute necessity for the possibility of any knowing whatsoever.

2. Immediate, Not Constructed, God-Consciousness

Vaiṣṇava epistemology further contends that awareness of God is immediate, not mediated through deduction or empirical inquiry. As Śrī Caitanya Mahāprabhu states:

nitya-siddha kṛṣṇa-prema ‘sādhya’ kabhu naya

“Love for Kṛṣṇa is eternally present within the living being; it is not something to be acquired from an external source.”

(Caitanya-caritāmṛta, Madhya 22.107)

This suggests that God-consciousness is not epistemically posterior but ontologically prior—a native orientation of the self, obscured by forgetfulness (apohanaṁ), but never extinguished.

This premise forms the core of the Vaiṣṇava preaching strategy: we are not giving people something foreign; we are assisting them in recovering what is already latent within them.

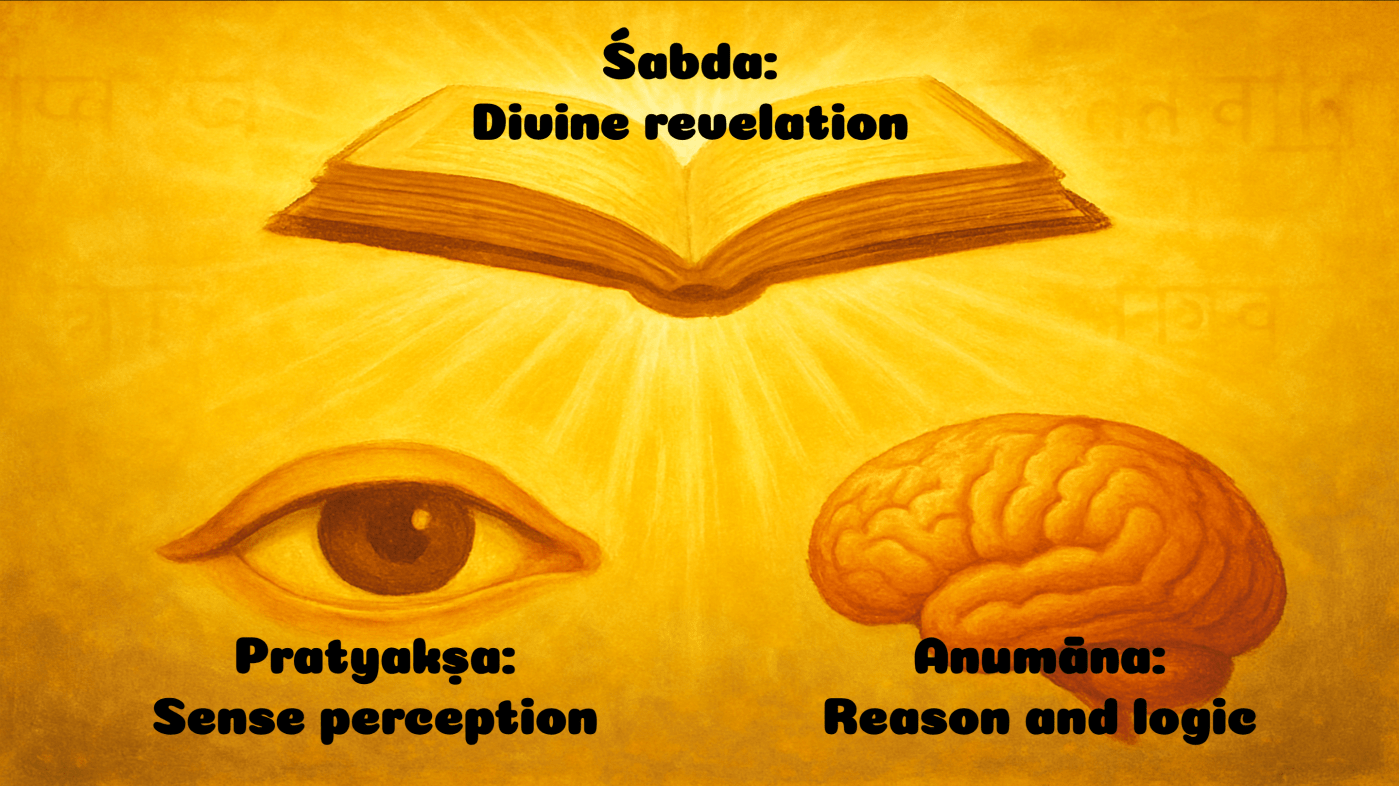

3. The Three Pramāṇas in Vedic Epistemology

The Vedic tradition accepts three pramāṇas—means of acquiring valid knowledge:

- Pratyakṣa – Direct perception through the senses

- Anumāna – Logical inference based on empirical observation

- Śabda – Authoritative testimony, especially from revealed scripture

While all three are acknowledged within Vaiṣṇava epistemology, they are not epistemically equal. Śabda holds epistemological primacy, particularly because of the inherent limitations of pratyakṣa and anumāna.

4. The Conditional Validity of Pratyakṣa and Anumāna

Pratyakṣa and anumāna, though useful, are epistemically derivative and not self-authenticating. Perception is prone to error, illusion, and incompleteness. Inference is dependent on the reliability of perception and the soundness of logical formulation—both of which are human faculties subject to fallibility.

More critically, neither pratyakṣa nor anumāna can provide an account of their own reliability without circular reasoning. To validate perception by more perception is question-begging; to defend logic by appealing to logic is to argue in a circle. This results in what philosophers call epistemic circularity—the inability to justify a system of knowledge from within itself. Without a transcendent source to ground these faculties, all such reasoning reduces to either pragmatism or skepticism.

Thus, both perception and inference presuppose certain metaphysical truths: the uniformity of nature, the reliability of cognition, the objectivity of logic, and the coherence of meaning—all of which apply not only to theological inquiry but to every domain of knowledge, including the empirical sciences. None of these conditions can be accounted for within a purely naturalistic framework. They require a foundation that is itself not contingent, mutable, or fallible.

Crucially, pratyakṣa and anumāna are only epistemically functional when subordinated to śabda. That is:

- When validated by śabda, perception and inference become meaningful and trustworthy.

- In the absence of śabda, they lose all authority, leading inevitably to epistemological skepticism.

This point cannot be overstated:

Only the acceptance of śabda grants conditional legitimacy to pratyakṣa and anumāna. Without śabda, one is left with zero pramāṇas—not two.

One might object that such a claim is equally circular: appealing to śabda to validate śabda. However, every epistemological system must appeal to some ultimate authority. The distinction here is between vicious circularity and transcendent necessity. Vaiṣṇava epistemology asserts that śabda is self-authenticating not arbitrarily, but because it proceeds from a perfect, omniscient, and benevolent source—Śrī Kṛṣṇa Himself. Thus, the circularity is virtuous and unavoidable, unlike secular rationalism, which is grounded in fallible human faculties and thus collapses into relativism or doubt.

Thus, the modern empiricist or rationalist who denies divine revelation is not standing on two pramāṇas; he is standing on none.

5. Śabda: The Epistemic Foundation

This is where the avaroha-pantha, the descending process of knowledge, comes into full prominence. Vaiṣṇava epistemology maintains that truth of any kind—whether moral, empirical, or theological—cannot be independently established through human speculation or sense perception alone (āroha-pantha). While such methods can yield practical insights, their validity and reliability ultimately depend, upon their alignment with śabda—authoritative revelation descending from a perfect source. In other words, all truth must be traceable to śabda to be epistemically justified.

Śabda, defined as āpta-vākya (speech from a perfect source), is the epistemic cornerstone of Vaiṣṇava philosophy. As Śrīla Prabhupāda repeatedly emphasized, the word of God is not subject to the defects that plague human cognition: illusion, error, cheating, and imperfect senses.

Śabda does not merely supplement reason and perception—it illuminates and corrects them. It is only through śabda that we can properly interpret our sensory experiences and apply reason meaningfully.

To use a classical analogy:

Senses and reason are like eyes, but śabda is the light by which those eyes can actually see.

6. The Transcendental Argument for God

This epistemological structure naturally leads to a formulation often called a transcendental argument—namely, that the very possibility of knowledge requires the existence of God. It can be logically outlined as follows:

- Knowledge exists. This cannot be meaningfully denied without self-contradiction, for even the act of denying knowledge presupposes the use of knowledge—of language, logic, and intelligibility.

- In order for knowledge to exist, there must be reliable epistemic faculties.

- These faculties can only be justified if they are grounded in an infallible source—śabda.

- Śabda requires a perfect origin, which is the Supreme Person, Kṛṣṇa. This origin must not only be infallible but also trustworthy. Trustworthiness entails intentionality, purpose, and moral reliability—qualities that cannot reside in an impersonal force or abstract principle. Therefore, the origin of śabda must be personal. Only a personal being, endowed with perfect knowledge and benevolence, can guarantee the authenticity, coherence, and relevance of revealed truth for finite, personal beings like ourselves.

- Therefore, knowledge is only possible if God exists.

The implication is clear: the atheist uses reason, logic, and moral judgment without being able to justify their existence or authority. He critiques theism while depending on the very things that only theism can account for. In this sense, atheism collapses into internal contradiction, while Vaiṣṇava epistemology offers a grounded, coherent explanation for how knowledge is even possible.

Preaching, therefore, is not only a proclamation of revealed truth but also an act of philosophical exposition—demonstrating the failure of alternatives and the coherence of beginning with God. Those who embrace this epistemology are not merely philosophers but agents of spiritual awakening. They do not argue for Kṛṣṇa as an idea—they reveal Him as the eternal foundation of all knowing, all meaning, and all love. The preacher must bring the listener to a crossroads: either accept the self-revealing authority of śabda, or face an endless regress of unjustified assumptions. This is what is meant by the phrase “the impossibility of the contrary”: without God, nothing can be truly known, affirmed, or justified.

7. Preaching Implications: Recovering Innate Theism

For those engaged in the preaching mission of Lord Caitanya Mahāprabhu, these insights are not merely abstract. They are deeply practical.

The preacher’s task is not to “convert” or “convince” by mere argument. Rather, it is to awaken the dormant God-consciousness already present in the heart. The means to do this is śabda—transcendental sound, received through disciplic succession and properly transmitted.

The Vaiṣṇava preacher does not argue toward God. He begins with God, and from that grounding, demonstrates the absurdity of all attempts to know anything apart from Him. Furthermore, the preacher should actively engage in demonstrating the impossibility of the contrary—that is, any worldview that begins from an atheistic or naturalistic premise—denying the ontological priority of God, meaning denying that knowledge of God is the necessary and foundational condition for the possibility of any other knowledge—cannot sustain a coherent theory of knowledge, truth, or meaning.

The rejection of God inevitably undermines the legitimacy of the very faculties one relies on to perceive or reason. In this way, Vaiṣṇava preachers are not only proclaiming the supremacy of śabda but are also exposing the internal collapse of all systems that attempt to operate independently of it.

Moreover, in addressing modern audiences, it is essential to recognize that resistance to God is not merely intellectual—it is volitional. The rejection of śabda is often accompanied by deeply rooted emotional or existential hesitations. Therefore, preaching must reach beyond surface-level refutation of ideas and appeal to the inner will of the soul, inviting a turning of the heart—not only a change of mind. This personalized, spiritually grounded approach enables Vaiṣṇava preaching to reach both the intellect and the heart—addressing not only conceptual confusion but also existential resistance.

8. A Critique of Godless Epistemologies

All godless epistemologies, including those that rely solely on sensory input or rational speculation, fall under the āroha-pantha and are therefore limited, fallible, and ultimately incoherent. The failure of these systems lies not just in their conclusions, but in their very method—seeking ultimate knowledge without submission to a transcendent source. This contrasts sharply with the avaroha-pantha, wherein the soul receives knowledge from the Supreme Person through śabda-pramāṇa—beginning with the innate śabda embedded within the self by the Lord, and continuing through externally transmitted revelation. In this way, all true knowledge, whether internal or external, arises from the descending current of divine communication.

From an epistemological standpoint, it is not enough to merely affirm the coherence of the theistic-Vaiṣṇava worldview. One must also show that only a theistic framework can account for the intelligibility of any knowledge claim—whether in science, ethics, or metaphysics—since all such domains rely on preconditions that only theism, and specifically Vaiṣṇava theism, can justify. One must also demonstrate the incoherence of all alternatives—not only because they are deficient, but because they rest on assumptions that are themselves dependent on the very theistic worldview they reject. Clarifying this not only refutes secularism but reveals how only Vaiṣṇava philosophy preserves the unity of experience, value, and meaning—across all disciplines and domains of thought. That is to say, atheism and naturalism do not simply fall short—they collapse under their own weight.

The modern empiricist claims to know reality through observation. But how can he account for the reliability of his senses without begging the question? The rationalist appeals to logic, but how does impersonal matter give rise to immaterial laws of logic that are universally binding? The moralist speaks of right and wrong, but what is morality in a world governed by impersonal chemical reactions?

In each case, the non-theistic worldview assumes the very things it cannot justify: reason, meaning, value, purpose, and unity in diversity. These are all epistemic and metaphysical categories that require a personal, intentional, and omniscient source—namely, Bhagavān Śrī Kṛṣṇa.

In contrast, Vaiṣṇava epistemology offers a unified field of explanation rooted in a single, unifying principle: the eternal, innate śabda revealed within the soul by the Supreme Lord. From this foundational knowledge, the soul’s intrinsic nature as Kṛṣṇa’s servant is made intelligible, the presence of Paramātmā as the inner guide is apprehended, and the validity of external śabda—scriptural revelation—is recognized. It is this inwardly embedded divine knowledge that enables all valid cognition, whether empirical, moral, or spiritual, and serves as the deepest epistemic foundation for meaning and truth.

9. Śabda or Skepticism: The False Neutrality of Secular Reason

Vaiṣṇava preachers must press the antithesis. There is no neutral ground. One must either begin with revelation (śabda) or face the abyss of skepticism.

Every attempt to construct a worldview apart from God ultimately relies on ungrounded assumptions—an irrational faith in reason, in sensory input, in human dignity, or in moral intuitions that cannot be justified within a materialist ontology. These assumptions are unjustified assumptions borrowed from the theistic worldview.

Therefore, the question must be forcefully presented:

If not śabda, then what? If not Kṛṣṇa, then who guarantees the truth of our knowing?

There are no alternative foundations. This is the impossibility of the contrary. The rejection of God is not a neutral act—it is an epistemic suicide.

10. The Moral Suppression of Divine Knowledge

Finally, Vaiṣṇava epistemology agrees with the epistemological insight that rejection of God is not merely intellectual—it is volitional and moral. The atheist does not lack evidence. He suppresses the truth that is already within him.

This is not to suggest that all non-believers are consciously dishonest, but that there is a deeper dimension of resistance operating beneath the surface. As Kṛṣṇa is situated in the heart, His presence and prompting are ever active. When rejected, this represents not just ignorance, but a willful turning away from divine revelation.

As the Bhāgavatam declares:

parābhavas tāvad abodha-jāto yāvan na jijñāsata ātma-tattvam (Śrīmad-Bhāgavatam 5.5.5)

“As long as one does not inquire into the Self, one is defeated in all his endeavors.”

This resonates with certain modern critiques of secular epistemology, which hold that all non-theistic worldviews are epistemically defeated because they refuse to submit to the ontological reality of the self and God.

The preacher, therefore, must expose not only logical flaws but moral rebellion. He must present śabda as both a source of knowledge and a call to surrender—an invitation to realign one’s life with the Absolute Truth. This moral dimension is essential to preaching: without it, epistemology becomes mere abstraction, rather than a transformative call toward spiritual restoration.

Conclusion: Revelation as the Only Sufficient Ground

Vaiṣṇava epistemology stands alone in its ability to account for the origin, structure, and reliability of knowledge. It affirms what all other systems must borrow but cannot explain: that the very possibility of knowing anything presupposes the reality of God and the śabda that proceeds from Him.

At the core of this system is not a construct, but a recovery—a reawakening of the eternal, innate śabda embedded in the jīva by the Supreme Lord. All other pramāṇas derive their meaning and legitimacy from this one transcendent source.

Every denial of God is, in the final analysis, a denial of the self. It is a moral and metaphysical revolt that leads not to freedom, but to confusion. Vaiṣṇava epistemology reveals that there is no autonomous knowing—only borrowed light, which either acknowledges its source or fades into darkness.

For the preacher, this is not merely a matter of argumentation. It is a sacred duty: to awaken others to the voice already speaking within them, and to lead them from skepticism to surrender—not to an impersonal truth, but to the all-attractive Person, Śrī Kṛṣṇa.

Therefore, the highest epistemic act is not skepticism, but śaraṇāgati—surrender. Through śabda we gain not only knowledge, but the highest object of knowledge: Kṛṣṇa Himself.

Leave a comment