By Ajit Krishna Dasa

It is important to acknowledge at the outset that many people have legitimate emotional and intellectual reasons to be suspicious of religion. Certain prominent theological systems promote the notion that God hates particular individuals or groups, withdraws His love from them, and condemns them to eternal punishment with no possibility of redemption. In such systems, divine love is conditional and retractable — and consequently, followers of these religions are often encouraged to withhold their compassion from those outside their belief system. This portrayal of God as selectively loving and eternally punitive leaves lasting psychological scars and colors the way many people instinctively react to any discussion of God or religion.

It is often assumed that people reject religion due to rational analysis. However, from a cognitive and neurological perspective, this assumption is questionable. In many cases, rejection of religion is not the result of reasoned argument but of reactive avoidance rooted in the deeper, more primitive layers of the human brain — particularly the reptilian brain (instinctive survival responses) and the limbic system (emotional memory and threat detection).

This explains why intelligent individuals often respond to religion not with curiosity but with defensiveness, mockery, or even hostility — classic symptoms of fight-or-flight activation. Below, we examine five common fears triggered by religion and how Krishna consciousness, when properly understood, not only avoids provoking these fears but actively resolves them.

1. Fear of Judgment: “If there is a God, I will be condemned.”

One of the most immediate fears associated with God is the fear of eternal punishment or rejection. For many, especially those with negative religious conditioning, the very idea of divine authority triggers guilt, shame, and dread. This is especially true if God is conceived as a wrathful, perfectionist judge.

Krishna consciousness directly undermines this fear by presenting God as Bhakta-vatsala — one who is affectionately disposed toward His devotee. The Bhagavad-gītā (9.30) famously assures us that:

“Even if one commits the most abominable actions, if he is engaged in devotional service, he is to be considered saintly, because he is properly situated.”

This is not a license for wrongdoing, but a recognition that transformation comes through devotion, not through condemnation. The devotee does not fear God’s judgment, because Krishna is not pleased by punishment — He is pleased by sincerity.

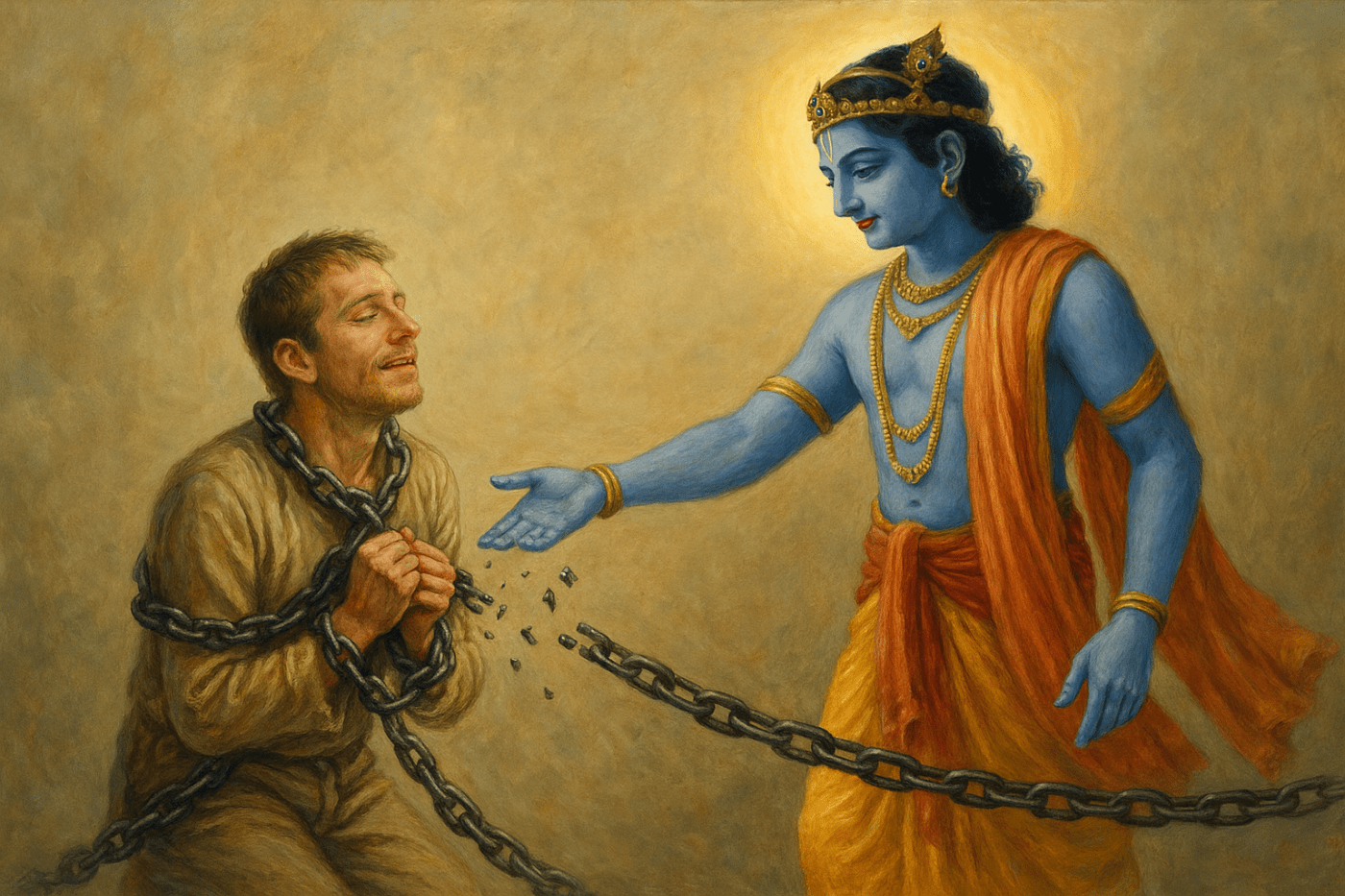

Moreover, the concept of eternal condemnation is absent in Krishna consciousness. While karma brings consequences, these are temporary and corrective, not eternal and vindictive. Even the worst sinner is not condemned forever but given opportunity after opportunity to awaken spiritually. The soul is never irredeemably lost, because it is eternally connected to Krishna.

Importantly, Krishna never stops loving the soul. His love is not withdrawn even from the most sinful being. The soul may turn away, life after life, but Krishna patiently follows, guiding from within as the Supersoul (Paramātmā), waiting for the moment the soul turns back. As stated in the Śvetāśvatara Upaniṣad (6.11):

“The Lord is the friend of all living beings.”

This divine love is not earned — it is intrinsic to Krishna’s nature. His mercy is causeless, and His efforts to reclaim the soul never cease.

2. Fear of Losing Autonomy: “I don’t want to surrender. I want to be free.”

This fear is deeply rooted in the modern secular psyche, which equates freedom with absolute self-determination. The idea of surrendering to God feels like a threat to personal agency. Ironically, this reaction is often driven by the reptilian brain’s territorial instincts: the desire to remain in control at all costs.

But Krishna consciousness redefines freedom. According to the Gītā (3.5, 3.9), every living being is already acting under compulsion — whether from the modes of material nature, psychological conditioning, or sense gratification. To “serve oneself” in this world is often just to serve one’s impulses.

Real freedom, Krishna says, is to act in accordance with one’s eternal nature:

“Such a person is truly free who has conquered desire and anger, and who acts with inner contentment, detached from material gain or loss.” (Gītā 5.26, paraphrased)

Rather than enslaving the soul, devotion liberates it.

This principle is echoed in many areas of life: freedom is achieved through discipline. A person cannot play a beautiful piece of music freely without first disciplining themselves to learn the instrument. Likewise, spiritual freedom comes from inner order and conscious restraint. Bhakti-yoga offers this spiritual training — not to diminish the self, but to empower it.

3. Fear of Authority: “I don’t want anyone controlling me.”

This fear often arises from negative experiences with abusive or authoritarian institutions, and it can be projected onto God. If all authority is presumed to be corrupt or oppressive, then surrender to a higher will seems like self-erasure.

However, the concept of divine authority in Krishna consciousness is non-coercive. Krishna is not a dictator; He is a loving, responsive person who gives complete freedom:

“As all surrender unto Me, I reward them accordingly. Everyone follows My path in all respects.” (Gītā 4.11)

The soul’s relationship with Krishna is based not on forced submission but on voluntary love. He does not compel; He invites. In the Gītā, even after instructing Arjuna thoroughly, Krishna tells him:

“Now deliberate on this fully, and then do as you wish to do.” (Gītā 18.63)

This is not control — it is relationship.

Even the laws of karma, which appear to be imposed from above, are ultimately designed to liberate, not subjugate. Krishna arranges the system of karma not to punish arbitrarily, but to guide each soul back toward its eternal, blissful function. As long as the soul acts against its true nature, it suffers. Krishna’s goal is not to dominate but to help each soul reconnect with its svabhāva — its eternal nature as a servant of God — which alone brings true happiness. The structure He gives is not oppression, but orientation.

For some, religion has been internalized as a source of psychological shame, leading to the belief that one is inherently bad, broken, or unworthy of divine love. This fear operates in the limbic system, which stores emotional pain and trauma.

Krishna consciousness challenges this narrative. The jīva, according to the Vedas, is nitya-siddha — eternally pure by nature, though temporarily conditioned. Śrīla Prabhupāda writes:

“The living entity is eternally the servitor of the Supreme Lord. Only in illusion does he think he is the master.” (Bhagavad-gītā As It Is, Introduction)

The path of bhakti is not about making someone feel worthless — it is about helping them recover their original dignity. This is not a superficial sense of self-worth based on ego or performance, but a deep rediscovery of the soul’s eternal position in loving service to Krishna. The very act of devotional service — hearing, chanting, offering, serving — purifies the heart and rekindles a sense of sacred worth. One begins to see oneself not as fallen and hopeless, but as beloved and reclaimable.

A powerful metaphor for this process is a child learning to walk. The child falls repeatedly, but no one says, “You’re a failure.” The parents encourage, smile, and cheer — because every fall is part of the journey. In Krishna consciousness, the same principle applies. We may stumble many times, but each sincere attempt is valuable. Krishna sees the heart, not just the outcome. As long as we keep trying, we are on the right path.

Rather than guilt-driven compliance, Krishna consciousness offers a path of joy-driven reawakening.

5. Fear of Losing Identity: “Will I have to give up who I am?”

This fear assumes that religion means becoming a faceless believer, losing all uniqueness and creativity. Again, this is a reptilian reflex to perceived identity loss — a deep existential anxiety.

But Krishna consciousness affirms and enhances individuality. The soul is not swallowed by God; it is eternally distinct yet connected. In Vaishnava theology, even in liberation the soul retains its form and personality. Śrīla Prabhupāda explains:

“The individuality of the living entity is always present… both in the conditioned state and in the liberated state.” (Bhagavad-gītā 2.12, purport)

Each soul is unique in its eternal qualities, preferences, and expressions of devotion. Just as no two leaves on a tree are exactly the same, no two souls have identical relationships with Krishna. Some souls serve Him as a friend (sakhya-rasa), others as a servant (dāsya-rasa), a parent (vātsalya-rasa), or a lover (mādhurya-rasa). Even within each category, there are limitless nuances. One soul may prefer to offer flowers, another to cook, another to sing, another to organize. Each soul has its own mood (bhāva), its own way of pleasing Krishna.

Thus, bhakti is not the negation of self — it is the perfection of self, in loving relationship with the Absolute Whole. Śrīla Prabhupāda explains:

“The individuality of the living entity is always present… both in the conditioned state and in the liberated state.” (Bhagavad-gītā 2.12, purport)

Thus, bhakti is not the negation of self — it is the perfection of self, in loving relationship with the Absolute Whole.

Conclusion: A Theological Cure for Fear

What people fear in religion — judgment, loss of freedom, control, shame, self-erasure — is not found in Krishna consciousness when it is authentically understood. These fears belong more to past traumas and neurological conditioning than to the teachings of the Gītā or the practice of bhakti.

And we must also acknowledge: much of this trauma has not arisen in a vacuum. Certain religious systems have historically promoted images of God as wrathful, condemning, and emotionally unstable — quick to love, quicker to hate, and merciless toward those outside the fold. In these traditions, hell is eternal, God’s love is finite, and the believer is taught to reflect that same conditionality. Krishna consciousness stands apart from this. It presents a God who never withdraws His affection, never stops trying to reclaim the soul, and whose system of justice is aimed not at punishment but rehabilitation.

Properly presented, Krishna consciousness does not provoke fear; it heals it.

It speaks to the soul, not to the reptile brain.

And when the soul hears, it rejoices.

Leave a comment