By Ajit Krishna Dasa

A New Law on Organ Donation in Denmark

As of June 1, 2025, Denmark has introduced a new law under which all citizens over the age of 18 are automatically registered as potential organ donors, unless they actively opt out. This system is known as a soft opt-out model: individuals are presumed willing to donate their organs unless they explicitly register otherwise. However, in cases where a person has not made a choice, family members may still be consulted before any organs are removed.

Shortly after the law came into effect, citizens received official notifications through their digital mailbox (e-Boks), encouraging them to log into the system and confirm their stance. Within the first month, over 260,000 Danes registered their decision—a record-breaking response that shows how important and personal this issue is for many people.

The law’s goal is to increase the availability of organs and reduce uncertainty in life-and-death situations. But it also raises profound ethical and spiritual questions: Should such a decision be made for you by default? What if your views on death, the body, or the soul go far deeper than the system can accommodate?

In what follows, I’d like to share my personal reflections on why I have chosen to opt out.

Not a Simple Decision

The question of organ donation is anything but simple. It must feel like an almost impossible decision—both for those who must consider giving and for those who find themselves in the deeply vulnerable position of hoping to receive. Although I might not think their decision wise, I empathize with people who choose to become donors—and with those who have received a new organ and been given the chance for extended life through that gift.

But when it comes to donating my own organs, I’ve chosen not to do so. This wasn’t a decision made lightly or impulsively. It’s the result of deep reflection—ethical, existential, and spiritual. I want to share some of those reflections here, in the hope of opening space for a more nuanced conversation.

When Are We Truly Dead?

One of the first questions in the debate around organ donation concerns the very definition of death. Most of us probably assume that organs are only removed once life is definitively over—and the heart has stopped beating. But in practice, organ donation almost always takes place while the body is still physically alive. The heart is beating, blood is circulating, and the body is kept warm and oxygenated by a respirator. The person is declared brain dead—but biologically, there is still life.

To me, this is clear: brain death is not the same as death. I’m not alone in thinking this. And who actually has the authority to define what death is? Well, God has, but no one wants to listen to Him, and therefore we find that there is certainly no universal agreement—neither among doctors, philosophers, nor ethicists. Many of them seem to expect that we should accept their definition … just because!

A Death Criterion Born of Practical—and Perhaps Economic—Needs

The concept of brain death was first introduced in the late 1960s. It wasn’t born out of a new understanding of death itself, but rather as a response to new technological possibilities. It had become possible to keep the body artificially alive with a respirator, even when the brain was irreversibly damaged.

But the real driving force behind the new definition was that transplant medicine needed better-quality organs. If one waited until the heart stopped beating, the organs were often too deteriorated to be useful. By declaring a person “dead” while their body was still functioning, organs could be removed under ideal conditions.

This raises an unavoidable question:

-Was this shift purely about care and saving lives—or did systemic and financial interests also play a role?

Transplantation is a high-tech, multi-billion-dollar industry. Hospitals and doctors receive funding and professional prestige through transplant programs. The more available organs, the better the system functions.

So it’s fair to ask whether the brain death criterion was widely adopted not because it brought us closer to truth, but because it solved a logistical and economic challenge.

For me, this is a serious part of the dilemma: when the definition of death is changed—not due to deeper scientific insight, but simply to meet the needs of a medical system—then trust becomes difficult. And at that point, I am out!

Is Consciousness Still Present?

Some of the most powerful testimonies I’ve encountered come from people who later regained consciousness after having been considered dying or even brain dead. They couldn’t move. They couldn’t respond. But they heard everything.

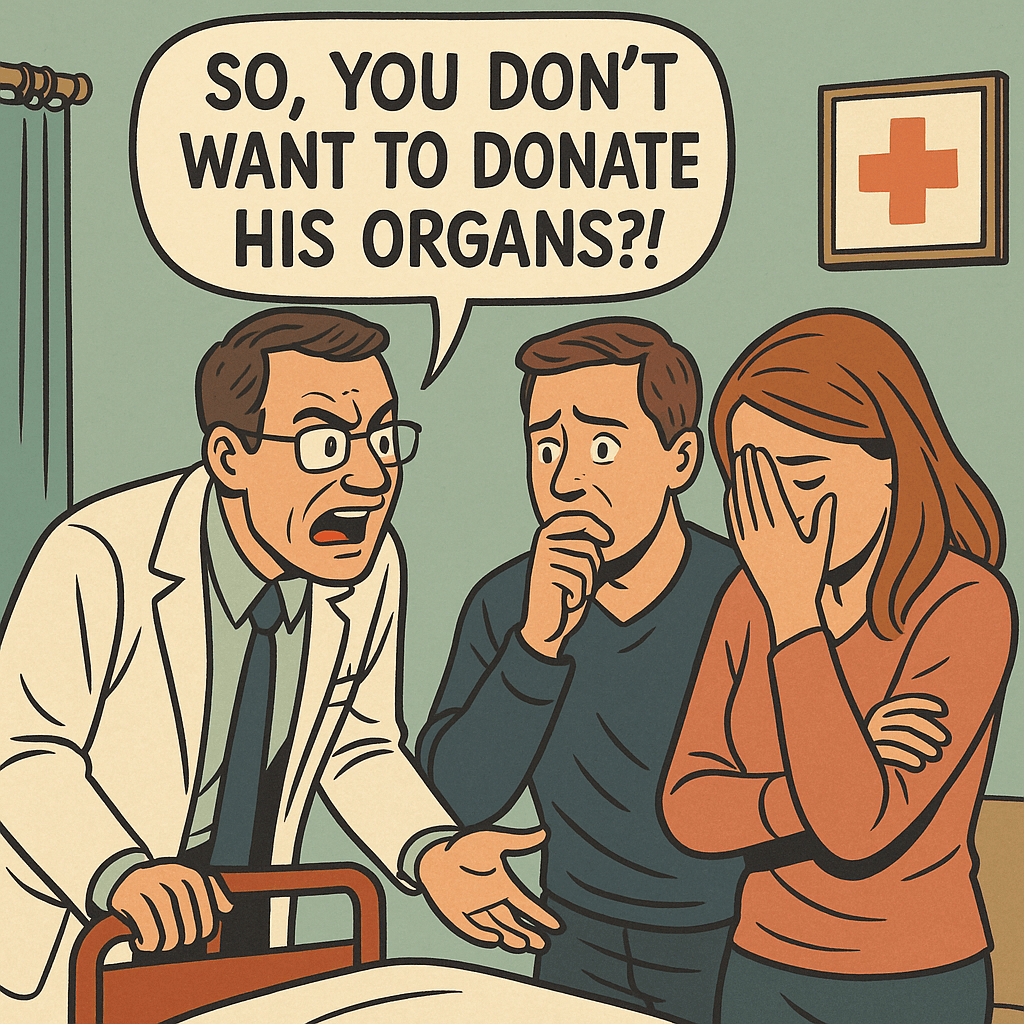

Some heard doctors speaking to their relatives, trying to convince them to withdraw life support and allow organ donation. They listened helplessly as their families were placed under emotional pressure to decide their fate—while they themselves lay trapped in a body that couldn’t respond, yet remained fully conscious inside. Clearly, they were not brain dead.

Imagine lying there, unable to open your eyes, unable to speak—while others discuss whether you should live or die, and which of your organs might be taken out and donated.

Today, we know that consciousness and inner awareness can persist even when all external signs of life have vanished. Neurological studies show that sometimes people in states close to coma or brain death can still hear and sense what’s happening around them—even when they don’t show any outward signs of awareness. This means that both laypeople and medical professionals may not understand the boundary between life and death as well as they think they do.

The Body’s Reactions During Organ Removal

Another thing that deeply affected me was learning how the body often reacts during organ removal. It is standard medical practice to administer anesthesia and muscle relaxants—even though the person has been declared dead.

Why? Because the body sometimes moves, tenses up, or jerks during the procedure. Some label these as mere reflexes—but to me, they look like resistance. A kind of physical protest.

And honestly—why would a dead body need anesthesia?

Even if there’s no definitive scientific proof that consciousness is still present, the fact that this is even a possibility should give pause. Is this a risk we’re expected to accept without question?

Death Is a Sacred Transition — Not a Mechanical Event

Now we’re entering the more spiritual part of my reasoning. I know that some may not value this perspective. And that’s okay — the arguments presented above already stand on their own. But for those who wish to go deeper, here is the spiritual foundation of my choice.

From the perspective of Krishna consciousness, death is not simply a biological endpoint or a moment defined by machines. It is a sacred transition — the soul (ātmā), which is eternal and conscious by nature, leaves the body and continues its journey according to the laws of karma and the will of the Supreme Lord, Śrī Krishna.

Śrīla Prabhupāda explains that the soul does not leave the body immediately at the time of clinical death. The moment of death is subtle and deeply personal, and any violent interference — especially cutting into the body while the soul is still partially present — can cause immense suffering and disturb the soul’s onward path. Therefore, from a spiritual standpoint, it is not only inappropriate but deeply harmful to treat the dying body as if it were already empty.

As a devotee, I do not want to leave this world in an atmosphere of machines, scalpels, and confusion. I want to leave it with the holy name on my lips and with Krishna in my heart — not on an operating table under fluorescent lights. My death is not just my end — it is my departure toward my next destination, and I want that transition to happen with dignity, peace, and spiritual consciousness.

My Choice — Grounded in Krishna Consciousness

For me, the choice is unambiguous: I do not wish to donate my organs. Not because I lack compassion, but because I understand — based on śāstra and the teachings of the ācāryas — that the soul is not the body. I am not this body. You are not your body. We are eternal, conscious beings, temporarily inhabiting material forms.

The body is Krishna’s property — not mine to dismantle and give away to “save the dress of a drowning person”. Śrīla Prabhupāda taught that the highest compassion is to help the soul reconnect with God, not merely to extend the mechanical functions of the body. Preserving spiritual integrity at the time of death is far more important than prolonging bodily existence at any cost.

Even scientific voices increasingly acknowledge that consciousness may not arise from matter. But whether science catches up or not, śāstra has spoken: the soul is real, death is a sacred passage, and disturbing that passage can have serious consequences for both the soul and those involved.

That is why I reject a death process shaped by confusion, speculation and economic interests. Instead, I choose a death guided by knowledge, surrender, and remembrance of Krishna.

Leave a comment