By Ajit Krishna Dasa

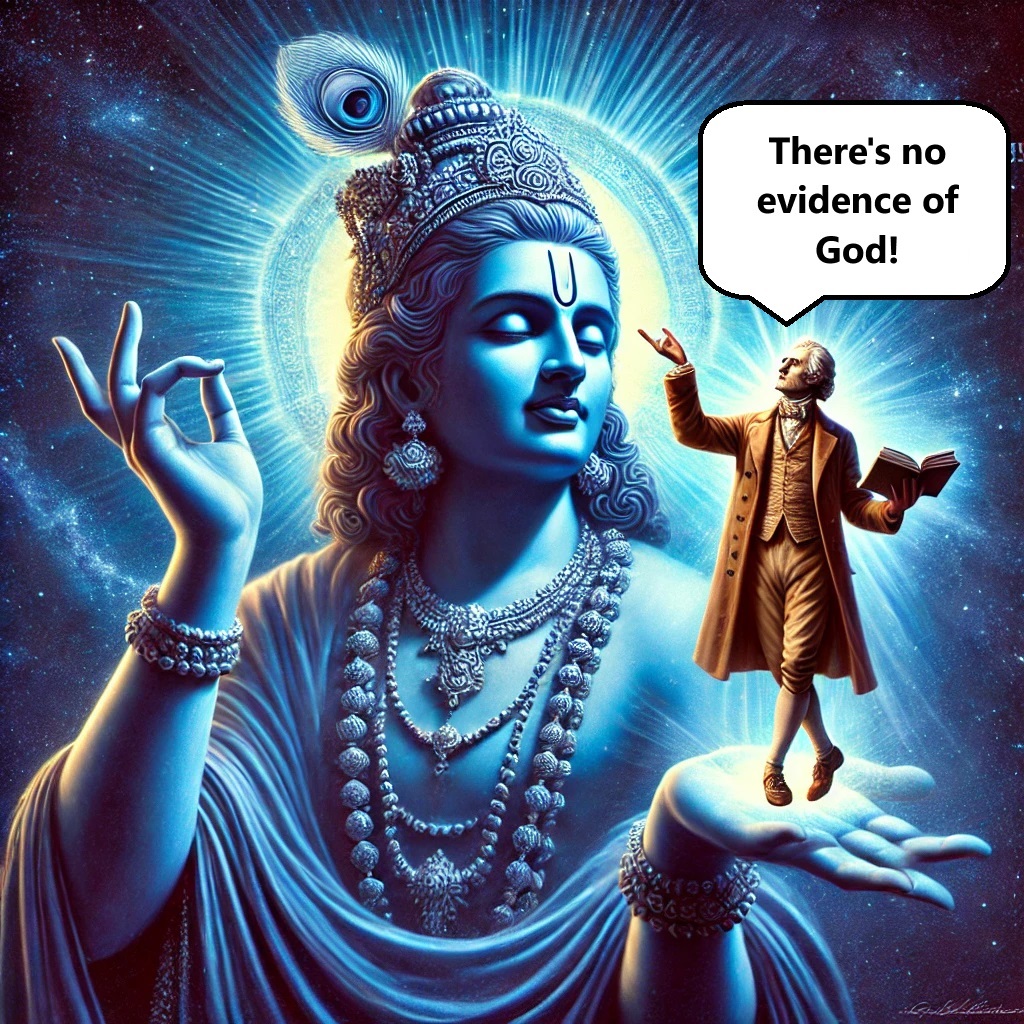

Anyone declaring “God does not exist” winds up contradicting him- or herself in at least four significant ways:

1) By inadvertently supporting the existence of objective values

Imagine this: an atheist boldly claims, “God does not exist.” In doing so, he’s not just speaking—he’s choosing. He’s decided to make this particular statement over countless other things he might have said or done. In effect, he’s valuing this assertion above all other actions. But here’s the twist:

atheism suggests that nothing inherently matters more than anything else—everything is equally valueless. So, why make a choice like this? It doesn’t make sense if all choices are equal. For value judgments to genuinely mean something, there must be an ultimate yardstick, a universal standard that all values can be measured against. Without it, values are just personal opinions, and it’s impossible to argue that one action is more valuable than another, or that anything has value at all.

Values are products of consciousness; they exist because we think and feel. They aren’t physical objects you can find or see; they don’t hang out on trees or wander the streets, and you certainly can’t spot them under a microscope. It’s clear then that imperfect, limited human minds can’t create absolute values or set up a definitive standard for measuring them.

Suppose we play along for a moment and agree that humans could establish absolute values. Even then, we’d hit a wall of contradictions. For instance, one person could declare it an absolute truth that human life holds immense value, while another might claim that the absence of human life is just as valuable. This would make human life both priceless and worthless simultaneously—a blatant contradiction.

The only reasonable explanation for absolute values lies in the existence of an absolute mind—God—who has the ultimate power to ensure that no one can modify or veto His established values. Thus, by stating “God does not exist,” an atheist inadvertently leans on the idea of absolute values that actually stems from a theistic worldview, unintentionally validating the existence of God and making their original assertion self-contradictory.

2) By inadvertently relying on the existence of truth, knowledge, and certainty

Consider this: when someone asserts, “God does not exist,” they’re making a bold statement of certainty—a definitive truth claim. But how does atheism provide a foundation for truth, knowledge, and certainty? If we ask an atheist how he’s certain of something (let’s say, A), he might explain that B causes A. Ask about B, and he’ll trace it to C, and so on. This line of questioning leads him down an endless spiral of causes without ever reaching a solid starting point to ground his claims to truth, knowledge, and certainty. The atheist might argue that his reasoning and sensory perceptions are the bedrock of his knowledge. However, since both are fallible, they’re not completely reliable. This means he might actually be mistaken about everything he thinks he knows. His only recourse to validate his reasoning and sensory perceptions is to use them, which sends him spinning into a circular argument—a classic logical fallacy.

To escape this loop, the atheist needs either to: 1) be all-knowing himself, or 2) derive his knowledge from someone who is all-knowing. This is because any knowledge he believes he possesses could be upended by undiscovered truths from beyond his reach.

Thus, claiming any solid grasp on truth, knowledge, or certainty without invoking an all-knowing deity is futile. By declaring “God does not exist,” the atheist paradoxically taps into the very concept of an all-knowing God. He borrows the very essence of truth, knowledge, and certainty from a theistic framework, contradicting himself yet again.

3) By taking the existence of the laws of logic for granted

Imagine trying to communicate without the guiding principles of logic—our conversations would devolve into indecipherable gibberish. Logic is the silent conductor of our thoughts, seamlessly orchestrating the flow of ideas and words. From the moment we start to form thoughts, our minds are tuned to the rhythms of logical laws. But can such abstract, objective, unchanging, universal, and eternal laws really spring from a purely materialistic, atheistic universe? The notion strains credulity.

Consider also our commitment to binary logic, where every proposition is stamped as either “true” or “false.” What if our natural world, or some cunning yet flawed entity, has tricked us into this binary way of thinking, while reality actually follows a more complex, multi-valued logic? Defending binary logic using binary logic itself spirals us into a dizzying circular argument. Breaking free from this loop would require guidance from an absolute being, endowed with ultimate power and insight—a concept comfortably housed within theism through its reliance on divine revelation. Atheists, lacking this option, unwittingly borrow their confidence in binary logic from theistic beliefs, thereby subtly endorsing the existence of God through their very use of logic.

This leads us to yet another intriguing contradiction in the atheist’s stance against the divine.

4) By banking on the existence of objective morality and ethics

Dive into any debate about God’s existence, and you’ll notice that even the staunchest atheist expects a fair play of honesty, logical reasoning, and civility. These expectations? They’re moral standards. But there’s a catch—under atheism, these moral benchmarks have no solid grounding. Without an absolute reference, morality is just a collection of personal opinions, rendering all actions morally neutral. It becomes nonsensical to champion one moral view over another, or even to adhere to any moral principles at all.

Thus, when an atheist clings to moral values during debates, he’s unwittingly laying claim to the very divine foundation he denies, borrowing from a theistic playbook to uphold his ethical debates.

Conclusion

Throughout this exploration, it’s clear that whether they’re outright deniers or fence-sitters waiting for evidence, atheists and agnostics unknowingly contradict themselves. They depend on abstracts like truth, knowledge, certainty, logic, and morality—concepts that falter without the pillars of a divine presence. By leaning on God to refute Him, they tangle themselves in a profound contradiction.

Here’s the twist: denying God requires an initial, albeit implicit, recognition of His existence. Logic dictates that if negating a proposition leads to contradiction, the proposition must be true. Therefore, “God exists” stands as a logical necessity, since its denial weaves into illogical absurdities. Despite this, driven by personal desires or biases, atheists might reject this conclusion, spiraling into a vortex of self-defeating arguments.

In essence, the very act of refuting God paradoxically anchors them in theism, revealing a hidden truth—they are, in fact, believers at heart.

To assert a propositional “truth” , one must assert an infallible revelation of propositions, and propositions can emanate only from a conscious being. The hypothetical atheist cannot assert , with any logical conviction, “God does not exist.” Sane “atheists” do not exist. They exist who claim one cannot know infallibly that an infallible revelation and so a Personal God exist.

All coherent thought of anyone must have logic based on accepted axioms. To claim no infallible knowledge means to claim no infallible axioms, Illogicality or madness characterizes the thought and stated propositions of the denier of infallible axioms and so the denier of an infallible Person, i.e. God, who has revealed such axioms. The infallible revelation of the book of “Ecclesiastes” teaches this as an infallible truth 9:3 ” This is an evil among all things that are done under the sun, that there is one event unto all: yea, also the heart of the sons of men is full of evil, and madness is in their heart while they live, and after that they go to the dead. “

LikeLike